- Home

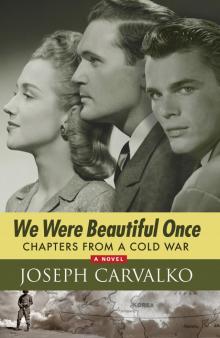

- Joseph Carvalko

We Were Beautiful Once Page 11

We Were Beautiful Once Read online

Page 11

***

Roger Girardin lived in a loft over a woodworking shop owned by seventy-year-old Solomon Carvahal, a Portuguese carpenter who had hired him in ’47 after Roger answered an ad in the New Haven Register. Carvahal had not asked to see a list of schools Roger went to or places he had worked; rather he asked to see something he made. When Roger opened the door to the shop, he heard a bell clang before inhaling an odor of wood and fish. His eyes adjusted to the natural light that funneled through a dirty skylight and lit up a floor rife in sawdust and a complement of machines: several jury-rigged saws, a lathe, drill press and three workbenches in front of a fat supply of lumber.

“Hello, anybody here?”

From behind a row of half built cabinets a small man—with a thin face and dark complexion and a kippah on his balding head—popped out. He spoke rapidly in an accent Roger heard only in the Bridgeport Jewish neighborhoods.

“Come, young man. Girardin, yes?”

“Yeah, that’s right. I called.”

He studied Roger before asking, “So what have you brought me to look at?”

Roger ripped the brown paper bags he had taped to cover a picture frame fashioned from cherry wood and propped it against a workbench, before pulling a hanky from his pocket and wiping it down. The old man moved back about ten feet and then tentatively walked forward, until he could smell the butcher’s wax, and removing his wire-rimmed glasses, he knelt down to eyeball the bold turns and twisting threads stitched in curving motifs. He had small, calloused hands and thin fingers that he ran over the polished finish—letting his hand freely twist and slide down the curvature of several faux spiraled flutes. His heart beat fast as he pulled a brass magnifying loop from his pocket, leaned in, lodged it into his eye socket, and stuck his little finger into the slippery scrolls, rosettes and twisted ropes sweeping effortlessly through a maze of tiny, hyperbolic French curves. Hunched a bit, he backed up, grasped the back of his neck, and smiled approvingly. The frame was just short of a masterpiece.

“Where’d you learn the craft?”

“My father, and for this I spent lots of time at the museum—looking at frames.”

“Well, young man, if I stand back, back where you’re standing, sides ain’t straight. Off by a few arc-minutes.”

“Arc what?” Roger came back nervously.

“You know, not squared. To the left.”

“I don’t see it.”

The man’s stare made Roger uncomfortable—like he was boring into his soul. In a slightly accusatory tone, he asked, “Are you interested in seeing it, young man?”

“I think so, if it’s there,” Roger replied, not sure what the man was talking about.

“It’s there. It’s there all right.” Roger heard certainty in the voice. “Are you interested in seeing it?” adding, “I need to know, up front.”

Roger heard water dripping from a faucet in the corner of the shop. “Yes, I am.” Then he looked at the man and this time with emphasis, affirmed, “Yes, sir. I am, sir.”

The old man put the back of his hand against his brow and let out a deep sigh. He knew the boy’s potential: a careful craftsman, who cared deeply, even passionately about the craft. But he had to hear him say “yes.”

“The inner eye, I call it, to see arc-minutes, to become aware, to see... to believe is to see. It’s not something that comes easily, takes years. Some never get it. You may never get it, ever. Takes an inner eye for things that are part nature, part us. Are you interested, young man?”

Roger rubbed his chin, not quite sure what to make of the old man’s rambling. “I never thought about it. But, look I’m out of work, I wanna make something. You have enough work?”

The carpenter leaned against a workbench. “There’s work enough for us who know our business. Have a seat. My name is Sol, Sol Carvahal.”

He pulled up a chair in front of Roger and the men got down to what Roger would do if he were to take the job, how he would be paid and what the old man could promise.

Roger summed up what he had heard. “You pay me a dollar an hour, sometimes I work eight hours, sometimes more. I can use the loft upstairs as my apartment. I get Friday afternoon from 2:45 to Monday morning off. I got to clean up every day—including the toilet—and if you ask me, I pick up lunch at the deli on Church.”

“Yep, that’s it. Oh, and unload the trucks when they deliver.”

“Sounds okay, I guess. I do what you tell me to.”

“Yeah, that’s it. Anything that needs to get done. And you learn how to be the best cabinetmaker in New Haven. I show you how to sniff out good oak from bad oak, dry from green maple... only the masters know. Sol himself will teach. You want it, young man?”

Roger looked, wide-eyed. His head, shoulders, upper body all said yes. “Yes, Mr. Carvahal, I’ll do it.”

“Call me Sol. I’ll call you Roger, make it easy?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Good, let start. Apron over there. Move in upstairs anytime, tonight, tomorrow, whenever. Oh... no women.”

Roger had been working in the shop nearly six months when one afternoon he returned with the deli order and heard the table saw screaming with Sol unconscious on the floor. He phoned for an ambulance. Sol had suffered a mild heart attack. Two weeks later the doctor released him from the hospital under orders to stay home for at least four weeks. He lived downtown, five blocks from the shop, in a four room, converted storefront that smelled of fried fish. Roger visited Sol every day to take direction on what to work on and saw to it that Sol ate three square meals.

On the day the old man returned to work, he looked like gray slate and seemed ten pounds lighter. His beady dark brown eyes focused on the shop floor, which Roger had cleaned and organized. He thanked Roger for being like a son and a partner during his recovery. The discussion led to Roger telling him about the work in progress and the deliveries ahead. At one point, Sol looked over at a black walnut music stand in the middle of the shop floor.

“I don’t remember an order for a music stand.”

“It’s for my girl. She plays violin. Thought I’d make it for her birthday.”

Sol walked over to inspect it. He ran his hands over the polished members held together through a solid design and a little glue. Then the centerpiece, a platen with a mirror-like finish for the music, furrowed and scrolled, its edge a crochet-like pattern to look filigreed, affixed to an adjustable, fluted, tapered stand that screwed into a base with three hand carved lion’s claws. On the back of the platen was a small engraved brass metal plate that read: “To Julie. Forever, Roger”

Affectionately, Sol looked at Roger. “You love her much, don’t you?”

“Someday we’re gonna marry.”

***

During the 1948–1949 college break, Trent invited Jack to a New Year's Eve party at the Pleasure Beach Ballroom—a large big band style dancehall on an island off Bridgeport.

“Hey, I’ve never met your sister. Bring her along.”

“Aww, she’s got a fella she’s goin’ steady with.”

“Have her bring him, too.”

When they arrived, a stream of people was funneling through the door, past an overweight cop checking IDs. Looking Julie over, the checker seemed to bare his belly as he insisted, “Little girl, you ain’t getting past me unless I see the right ID. Now move along.”

The three were huddling from the sting of a steady wind off the sound, plotting to get Julie in, when Trent and Tracy drove up in the red Mercury. When they reached the entrance’s barrel-shaped awning, they walked over to the threesome. After introductions, Jack explained the problem with the cop; suddenly it became Trent’s problem, because Tracy was also underage. Without hesitation, Trent pulled a twenty from his wallet, walked over to the guard and said that he was the guy throwing the party, and he needed to have his two sisters there when his parents arrived. The cop glanced around, shook Trent’s hand, folded the bill into his palm and gestured the group into the ballroom.

> Though Trent had hired a six-piece band to play until the early morning hours, he spent most of his time, not on the dance floor, but sitting with Julie, Roger and Jack. He seemed not to notice Anna or the other three dozen friends that he had invited. None of them could help but notice that Trent was captivated by Julie; he would not let her out of his sight. Wearing a sapphire blue silk cocktail dress, her hair swept up on the sides with long pipe-curls and a borrowed pair of rhinestone-studded earrings, Julie was as beautiful as any girl in the room. What was more, she was in love. But seeing an opening, Trent asked Julie about school, music, hobbies and engaged her in nonstop, yet polite, conversation. Roger was usually unruffled by the attention men showed Julie. There was something special about her, for those who took the time to look twice, and he was proud that she was his girl. But when Trent asked Julie to dance—a slow dance—Roger straightened his tie and met Trent’s eyes dead-on.

“You don’t mind, Roger, do you?” Trent smiled, while reaching for Julie’s hand.

Roger, brushing off what he knew was a pass, answered, “Mind? Julie’s a big girl—she dances with who she wants.”

For a split second, Julie felt the scene go tense, but her hand was already extended in Trent’s direction. Roger focused on the couple as they embraced on the floor. The lights were dimmed, a rotating mirror ball in the center projected sparkling flickers throughout the hall and Julie looked for Roger as Trent spun her around, but Trent moved her to the far end of the kaleidoscopic ballroom. Halfway through “I Can Dream, Can’t I,” Trent asked her to a movie or dinner. It would not be possible, she explained—she and Roger were steadies. Claiming he hadn’t known, Trent left the offer open should she change her mind. Following the dance, Trent disappeared until midnight, when “Auld Lang Syne” brought everyone together under a storm of confetti and favors.

Later,Trent told Jack he had not realized his sister was “a knockout.” Jack had never considered Julie anything but average, but Trent suggested that the next time they returned from school that Jack and he take their sisters out for the night and get to know each other. Jack did not feel one way or the other about Trent’s attraction and left it at that.

At the end of February, the boys returned home on college break. Trent asked Jack and Julie to dinner at the mansion. They had the whole house to themselves—the older Hamiltons having ventured to Palm Beach. Instead of dinner, they had pizzas and beer. For Julie this was new, as she had few friends—especially friends with homes with huge pillars out front. After eating, the group ventured into the gameroom to play pool, Trent put on some music and it wasn’t long before he and Julie were dancing. Trent being Trent, he held her close, and Julie being Julie, it made her uncomfortable. She lightly pushed back, her floor maneuvering unnoticed by her brother. About mid-way through the evening, Tracy disappeared with Jack, who hadn’t noticed her attempts to out maneuver Trent on the dance floor. Julie found herself alone with Trent. When she leaned over the pool table, he grabbed her by the waist and pressed against her, kissing her neck. She turned abruptly, red-faced, and pushed him off.

“No, Trent. I can’t. You’ve been drinking too much.”

“Hey, what’s wrong? C’mon, girl, I can show you a really good time.”

“Look, I don’t know you, and I’m not interested right now.”

“Is it that loser, what’s his name? He doesn’t have anything I don’t got. Hah.”

“Roger’s no loser, he’s a... ” Julie broke off. What she saw in Roger was her treasure, hers alone, and she wasn’t about to share it or justify it to Trent. “I’m saying, I have a boyfriend.”

“God help you, girl, look around.”

Four weeks later, Julie received an unexpected call.

“Trent? You looking for Jack? I thought he was there with you, up at school!”

“No... looking for you.”

“What’d you mean?”

“Julie, about that other night.”

“Trent, let’s just forget—”

“Julie, hear me out, I can’t take no for an answer. All I do is think about you.”

“Please, Trent, that’s flattering, bu—”

“Next time I come home, I’d like to call.”

“I can’t stop you, but I’ll always be straight with Roger.”

***

Trent invited Jack and Julie, together with Roger, to a Memorial Day pool party. Julie agreed, wanting to appease Jack and maybe even to demonstrate that she and Roger were a couple. Except for a slight twitch to his smile and an extra, unnecessary pressure in the handshake he offered Roger, Trent’s face revealed nothing. He was the perfect Hamilton host. The guys talked sports and cars, while the girls, sitting on the other side of the pool, talked about school and boys. As the evening progressed, Trent and his friend Gallagher started in on a ’34 Chevy that they had souped up and then crashed and ditched at the sand banks one night.

“Hey, Roger, you know anyone with a clunker they want to get rid of?” Gallagher asked.

Taken by surprise, Roger answered, “The guy I work for has a ’37 Packard he never uses. It’s just sitting in the lot behind his shop.” Before the words were out of his mouth, he regretted having said anything at all.

The following week Trent and Gallagher asked Roger if they could see the car, and wishing again he had kept his mouth shut, Roger invited them over. If they were really interested, he would ask Sol if he wanted to sell it. On Saturday night, Trent, Gallagher and Steve Boddie drove up in Boddie’s new Plymouth coupe. Roger brought them around the back of the shop where the car sat in an otherwise vacant lot.

“Hey, Roger, mind if we start it up?”

“I don’t think we should do that, not sure Sol would like it.”

“Come on. Got the key?”

“Inside the shop.”

“Go get it, let’s just turn her over, that’s all.”

Roger went to the shop and retrieved the key from a hook behind Sol’s desk.

“The battery’s sure to be dead,” Roger said.

“Get that coupe over here, we’ll jump it,” Trent said, pointing to the Plymouth.

Roger stepped out of the way, while Boddie moved his car in position. Gallagher popped the hood on both cars. A minute later, the old Packard turned over. Trent, behind the wheel, shifted in reverse, floored the gas. The car jerked back.

“Hey, hold on there,” Roger protested.

“I’ll just take it for a spin, Roger-boy. Be right back, don’t worry. Boddie, follow me in case I get stuck.”

“Trent, get that goddamn car back here. I’m going to get fired if my boss gets wind of this.”

But Trent was already halfway out the back lot, Boddie and Gallagher in tow. An hour passed, and the Fairview boys hadn’t returned. Roger went into the shop and went to the loft to lie down to a restless night.

The next day, Sunday, he stayed in New Haven rather than make the weekly trip to Bridgeport. He tried to contact Trent. Later that night, Jack called to tell him that while his friends were joy riding, the car went off the road and crashed somewhere north of New Haven. The boys had abandoned the vehicle where it had come to rest.

When Trent, Gallagher and Boddie were arrested a few days later, old man Hamilton’s lawyers launched a full scale attack claiming that Trent had had Roger’s “permission” to take the car for a test drive. As Trent later told Boddie: “This guy ratted me out. He’s gotten in my way once too often, first Julie, now this. This won’t be forgotten. Next time, I’m going to beat that bastard to a pulp.”

On the day Trent and his old man went to court, people with legal problems were standing in the aisles, jamming the courtroom doorway, bobbing, turning, listening for a familiar name, or even their own. A rap on the oak door behind the bench signaled Judge Miniter’s entrance. Everyone stood as a diminutive, black-robed man emerged from behind a door, commanding, “Sheriff, open court!”

The prosecutor, a skeletal young man in his mid-twenties, stood next to a shel

lacked wooden table with two stacks of manila files. He reached for a folder, and in the timbre of a teenager said, “Your Honor, the State calls... ”

Forty minutes later the prosecutor had cleared the docket and, having no more defendants in the stack, approached the judge. “Sir, it’s the Hamilton case up ne—” and whispered something.

“Sheriff, clear the room,” Miniter commanded, cutting him off.

The proceedings took two minutes, but Trent—his particular sense of loyalty offended, wasn’t about to let things go as easily as the judge had been persuaded to. He seethed, vowing that the time would come to get even with old Roger.

Until It’s Time to Go

ONE CHILLY MID-DECEMBER AFTERNOON in ’49, while waiting on the steps of the museum, Julie saw Roger a block away and started running, oblivious of the Santas ringing bells in front of red and green buckets of money and bumping past shoppers, until she threw her arms around his neck. Taking her soft cheeks in his hands, he kissed her. They took a stroll to East Rock Park on the north end of Yale’s campus. She leaned against a large boulder, and Roger embraced her tightly, blanketing her body with his.

“You’re the first guy I ever had a crush on, you know,” she said. “Never dated anybody, except when I went to a freshman dance once.” Roger listened, kissing her gently on the neck. Eyes open, looking straight ahead into a thicket of yew, she continued, “I just never drew any attention.” Roger did not answer, his fingers—rough from shop solvents—moved under her sweater feeling her smooth breasts. “Always thought I was too plain. Do you think that’s weird?” Roger rubbed his palms on her back then her stomach. She felt him press against her. “And in school it seemed when anybody found out I played the violin, they ran away, like I had the plague or something.” Roger’s body began to move slowly, arcing against hers. She pushed him away looking beyond the yews. “Roger, be careful, someone might be watching.” He turned down the corners of his mouth and furrowed his eyebrows. She burst out laughing. “How come you’re so attracted to me? Well, why?” Roger was at a loss, trying to regain some measure of self-possession.

We Were Beautiful Once

We Were Beautiful Once